It’s amazing how quickly our lives scutter into insignificance. The bare facts of our existence only traceable through faded documents, and increasingly, inaccessible files in ancient computer programs: less decipherable after ten years of tech innovation than an Egyptian hieroglyph after a thousand. Whether the internet will have a more preservative effect on the ephemera of our day to day existence over the long term remains to be seen, but perhaps its very abundance will render this detail worthless, unlike the crumbling relics of the physical past we must handle with care.

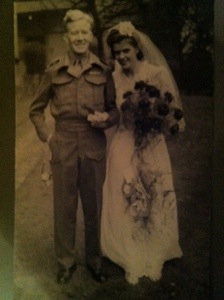

How quickly we move on was marked or me by the recent death of my grandparents. Charles ‘Ted’ and Ethel Franks. Already so little of them remain. I know where they were cremated – Medway Crem – and have some pictures, but they left nothing behind but their genes. My grandad’s way with numbers and hunched boniness has shuffled on in Jonah, as has his flaxen hair, said to come from his mother’s one night encounter with a Norwegian sea captain, but more than likely a fluke from Chatham. Luckily for my son, Ted maintained it to his death, giving Jonah some faint hope, although his own son, my father, lost his at 17. But the fact is, Ted didn’t know who his father was, and now no one ever will.

Ethel too, once a Rowley from Nottingham, had two sisters but even I don’t remember their names. One – was she Margaret? – died young, and so we never met her, but gave my own sister her tumbling curls, which Katie has straightened the fuck out of since the dawn of GHDs. The other, I remember from a couple of stifling visits to the nursing home up the road. My first encounter with extreme old age, but not the last. Was their father called Hopwood; a watchmaker? I’m not sure but I know if I don’t ask my own Dad, an audio inventor who lives in Kent who spends most of his time in the Far East with his latest wife, soon, that too will be lost to time.

I don’t know why I feel the need to put these facts in some sort of digital glass cabinet. I have scant need for my live relatives, let alone those that are dead. My family tree has seeded itself at will, with little thought to cultivation over the years. First families have yielded to second marriages, halves and steps abound with little in common save a replica dimple here, a keen eye for detail there , or the bedroom mirror of my youth that once reflected my stormy adolescence and now stoically bears witness to another’s.

Members from all sides have remade themselves half a world away, not once but many times. My family history is marked by transience, by failing to leave something behind for the next generation – in my mother’s case, by cruising away her Baby Boomers’ inheritance. It’s not a distinguished line I come from. We’re just ordinary people subject to the same tidal pull as anyone else.

But I want to create more of an identity for my own progeny. Luckily, for me, Ma’s generous retirement in sunny Florida has given her the time and resources to do a little digging for me, and she has unearthed, if not exactly a family gem, then at least a tangle of roots.

There was some poetic circularity in the discovery that my great great grandparents once lived in the Peabody tenement in Cambridge Crescent, Bethnal Green, just a stone’s throw from the site where I once kept my own head above water when I first moved to London. Once called the Arabian Arms, the pub’s building was rebuilt the year after the census named Fred and Mary Frances Legon as local residents, though it was almost certainly a place of ill repute, it would go on to become a strip club. Now known as the Metropolis, or as Tom once fondly called it, the Met Bar East, where we met, back when I was a dancer, or the latest version of East End hustler trying to make ends meet.

It’s no great surprise the Legons fled to Canada soon after, where they prospered, having suffered East End deprivation at it’s height. It’s hard to reconcile this ignominious background with my memories of my grandma from Canada, their last daughter, Connie, a bright eyed stylish woman who stayed birdlike to the end. Neat as a pin, it’s from her I get my propensity to OCD. But her legendary stinginess was no doubt the result of generations of thriftiness that saw the family through hard times. The colourful streets of Bethnal Green, documented here in lively detail, were squalid, a place where desperate people washed up and those that could, escaped. And yet, that line stayed put for generations, scratching a living as Thames watermen since the 1600s around Shadwell which was to become a social wasteland before the docks shut and it became an industrial one.

But back in 1670 when Sarah, late wife to one John Salsbury married her second husband Thomas Gleghorne, it was a semi rural thoroughfare in the hamlet of Stepney Green. It was to become once of the poorest districts of London, a brief history of which is detailed here. There is little doubt I have thieves and vagabonds in my blood, prostitutes, paternal cultural interlopers from local local drinking dens who made their way, by maternal deception into my blood, society’s flotsam and jetsam washed up on the shores of the Thames. It is little surprise that I ended up here too. My take-no-prisoners feistiness, a testament, no doubt, to my East End heritage has seen me among the new influx of sharp elbowed middle classes to the area, who fight tooth and nail for a place on its competitive property ladder, but who are able to overlook the shabbiness that remains of its rough, tough past.

But my East End ancestors were survivors too, the ones who weathered harsh winters without hurling themselves off the local “Bloody Bridge”on Ratcliffe Highway, who pulled through encounters with typhoid, plague, jigger gin and local tyrants: they were no doubt a hardy bunch. But the saddest case I know if one of my more recent descents, a great great uncle, Sidney Frederick Legon, the second boy in the family group, who having made it as far as Canada, left his 17 year old bones in an unmarked grave in France. His attestation papers into service gave his birthplace as Stepney Green and his occupation as a weaver. What would he have become if he stayed? Probably the same brutal fate would have awaited.

On the other side, a whole clutch of Cargills lived on what was to become a bomb site just behind the canal side town house I now call home. No better than they ought to be, they can be traced back to Kirriemuir, Angus, Scotland in 1732, near Glamis Castle. This is my one spurious claim to nobility, but itself infamous for tales of monstrous aristocratic inbreeding, whose descendants, first cousins to the queen were left to rot in institutions because their gene pool hadn’t been allowed free rein, but yet all of whom bear a passing family resemblance, perhaps from a common ancestor many centuries hence. It is perhaps better for me that my more immediate forbears knocked around the agricultural hinterland of Mile End Old Town in the 1800s, marrying girls for the local workhouses, who would be at the very least, fairly disease resistant.

And somehow, they made out okay. On the Cargill side, George looks debonair but rakish in his picture taken in his 70s – a likely product of multicultural Mile end for all his Scottish ancestry while his wife Ada, born Swait is a true English rose, whose Devon roots are as plain as the nose on her face, one my own mother has always decried on hers.There are still Cargills in Kirriemuir today, the most famous of whom, Karen, could pass for my mother. Does a common relative explain why I love to sing and Jonah can hit a pitch that could shatter windows. I certainly hope so, but we’ll never know.

And in the pictures of the last Legons to whom I can claim direct descents, Frederick is dark eyed and handsome, hardly the Anglo Saxon pedigree his tree, on paper might lay claim to, nor the victim of extreme poverty his census time lodgings would suggest, although he looks painfully young to be the father of three. His wife, Mary, once a Phillips, looks stern, but well-kempt for all the lore of her flaming red hair, and the fact she already has three kids under five. Only three of their eventual five children would go on to have children of their own; the youngest, my grandmother, Constance.

These unknown figures are our alpha and our omega – their traits, quirks, talents and longevity live on in my children, and are as much to blame for Jonah’s quick temper and charm as anything I’ve handed on. We can only speculate about the details of their existence and preserve what few facts we have, but they tell us more about who we are today than many of us would like to admit. But in more senses than one I’ve come home to roost my the East End backwater, and can lay claim to being a thoroughbred cockney: that is, an outsider and a mongrel, a victim of circumstance but a robust product of survivor’s genes.

But these faded photographs remind us too that we should pay more attention to the relatives that remain, even if they remind us too strongly of ourselves, of how we too will end up with time. We must record their stories, and note down their relationships, because after they are gone, it’s surprising how quickly this detail dies too. For we all die twice. Our second death occurs when the last person who remembers you shuffles off their mortal coil, when the last photo fades, when your social media cache gets emptied, software, then hardware becomes redundant, and you become a mere statistic, the ghosting milling crowd who make up a generation, a society, an era: history. So we have to trust in our daughters and sons, and their own, to look after our memories just as we helped form theirs for them.

Discover more from Looking at the little picture

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.